From NewYorkMetro.com

The week of September 11 (two weeks ago, not five years), I noticed a poster up at Frankies, my sweet neighborhood trattoria in Brooklyn: It advertised a talk on 9/11 by Daniel Pinchbeck—the former downtown literary impresario who has become a Gen-X Carlos Castaneda and New Age impresario. My breakfast pal nodded at the poster and said, “The guy is selling his apocalypse thing hard.”

“Apocalypse thing?” I knew of Pinchbeck’s psychedelic enthusiasms, but I’d somehow missed his new book about the imminent epochal meltdown. In 2012, he interprets ancient Mayan prophecies to mean “our current socioeconomic system will suffer a drastic and irrevocable collapse” the year after next, and that in 2012, life as we know it will pretty much end. “We have to fix this situation right fucking now,” he said recently, “or there’s going to be nuclear wars and mass death … There’s not going to be a United States in five years, okay?”

The same day at lunch in Times Square, another friend happened to mention that he was thinking of buying a second country house—in Nova Scotia, as “a climate-change end-days hedge.” He smirked, but he was not joking.

On the subway home, I read the essay in the new Vanity Fair by the historian Niall Ferguson arguing that Europe and America in 2006 look disconcertingly like the Roman Empire of about 406—that is, the beginning of the end. That night, I began The Road, Cormac McCarthy’s new novel set in a transcendently bleak, apparently post-nuclear-war-ravaged America of the near future. And a day or so later watched the online trailer for Mel Gibson’s December movie, Apocalypto, set in the fifteenth-century twilight of, yes, the Mayan civilization.

So: Five years after Islamic apocalyptists turned the World Trade Center to fire and dust, we chatter more than ever about the clash of civilizations, fight a war prompted by our panic over (nonexistent) nuclear and biological weapons, hear it coolly asserted this past summer that World War III has begun, and wonder if an avian-flu pandemic poses more of a personal risk than climate change. In other words, apocalypse is on our minds. Apocalypse is … hot.

Millions of people—Christian millenarians, jihadists, psychedelicized Burning Men—are straight-out wishful about The End. Of course, we have the loons with us always; their sulfurous scent if not the scale of the present fanaticism is familiar from the last third of the last century—the Weathermen and Jim Jones and the Branch Davidians. But there seem to be more of them now by orders of magnitude (60-odd million “Left Behind” novels have been sold), and they’re out of the closet, networked, reaffirming their fantasies, proselytizing. Some thousands of Muslims are working seriously to provoke the blessed Armageddon. And the Christian Rapturists’ support of a militant Israel isn’t driven mainly by principled devotion to an outpost of Western democracy but by their fervent wish to see crazy biblical fantasies realized ASAP—that is, the persecution of the Jews by the Antichrist and the Battle of Armageddon.

When apocalypse preoccupations leach into less-fantastical thought and conversation, it becomes still more disconcerting. Even among people sincerely fearful of climate change or a nuclearized Iran enacting a “second Holocaust” by attacking Israel, one sometimes detects a frisson of smug or hysterical pleasure.

As in the excited anticipatory chatter about Iran’s putative plans to fire a nuke on the 22nd of last month—in order to provoke apocalypse and pave the way for the return of the Shiite messiah, a miracle in which President Ahmadinejad apparently believes. Princeton’s Bernard Lewis, at 90 still the preeminent historian of Islam, published a piece in The Wall Street Journal to spread this false alarm.

And as in Charles Krauthammer’s column the other day: He explained how a U.S. military attack on Iran would double the price of oil, ruin the global economy, redouble hatred for America, and incite terrorism worldwide—but that we had to go for it anyway because of “the larger danger of permitting nuclear weapons to be acquired by religious fanatics seized with an eschatological belief in the imminent apocalypse and in their own divine duty to hasten the End of Days.” In other words: Ratchet up the risk of Armageddon sooner in order to prevent a possible Armageddon later.

I worry that such fast-and-loose talk, so ubiquitous and in so many flavors, might in the aggregate be greasing the skids, making the unthinkable too thinkable, turning us all a little Dr. Strangelovian, actually increasing the chance—by a little? A lot? Lord knows—that doomsday prophecies will become self-fulfilling. It’s giving me the heebie-jeebies.

More here

Thursday, September 28, 2006

Monday, September 25, 2006

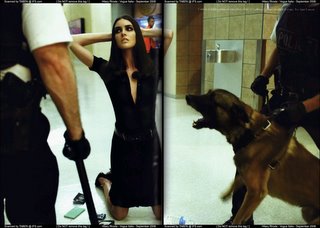

The Atrocity Exhibition, the Death of Affect, Vogue Italia and Terror Porn

Terror has become a self-replicating media virus. Al-Qa'ida snuff movies inspire imitative acts of barbarism. It's hardly surprising that the sadism of Abu Ghraib has been appropriated by terminal hipsters hard-wired into the Apocalyptic Zeitgeist. This month's Vogue Italia testifies to this rapidly-metastasising culture of cruelty. It features an, ostensibly, incendiary photoshoot from Steven Meisel. State of Emergency recycles, at least one of, the truly shocking images from Abu Ghraib (themselves "inspired" by violent pornography) into fashionably fetishistic soft core porn that both trivialises terror and de-sexes sex. Stark sadism eviscerated, re-configured and re-branded as a slick, hyper-sexualised advertising campaign featuring emaciated models subjected to imagined ordeals at the hands of faux-sadists. As Mark Fisher (k-punk) observes at Ballardian.com: "The overt sexualisation and compulsory carnality of postmodern image culture distracts us from the essential staidness of its rendition of the erotic." In our celebrity-obsessed, consumer culture the "banalification" of evil is, seemingly, endemic. Atrocity rendered anodyne. "The atrocities of September 11th and Abu Ghraib mimetised in the alternate death of Paris Hilton."

Meisel's photos can be found here.

Synchronously, I'm re-reading J.G. Ballard's perversely prescient and prophetic 1960s' novel, The Atrocity Exhibition right now:

Dr. Nathan gestured at the war newsreels transmitted from the television set. Catherine Austin watched from the radiator panel, arms folded across her beasts. "Any great human tragedy - Vietnam, let us say - can be considered experimentally as a larger model of a mental crisis mimetized in faulty stair angles or skin junctions, breakdowns in the perceptions of environments and consciousness. In terms of television and the news magazines, the war in Vietnam has a latent significance very different from its manifest content. Far from repelling us, it appeals to us by virtue of its complex of polyperverse acts. We must bear in mind, however sadly, that psychopathology is no longer the exclusive preserve of the degenerate and the perverse. The Congo, Vietnam, Biafra - these are games that anyone can play. Their violence, and all violence for that matter, reflects the neutral exploration of sensation that is taking place now, within sex as elsewhere, and the sense that the perversions are valuable precisely because they provide a readily accessible anthology of exploratory techniques. Where all this leads one can only speculate....

Sex, of course, remains our continuing preoccupation. As you and I know, the act of intercourse is now always a model for something else. What will follow is the psychopathology of sex, relations so lunar and abstract that people will become mere extensions of the geometries of situations. This will allow for exploration, without any trace of guilt, of every aspect of sexual psychopathology. Travers, for example, has composed a series of new sexual deviations, of a wholly conceptual character, in an attempt to surmount this death of affect. In many ways he is the first of the new naives, a Douanier Rousseau of the sexual perversions. However consoling, it seems likely that our familiar perversions will soon come to an end, if only because their equivalents are too readily available in strange stair angles, in the mysterious eroticism of overpasses, in distortions of gesture and posture. At the logic of fashion, such once-popular perversions as paedophilia, and sodomy, will become derided clichés, as amusing as pottery ducks on suburban walls."

The "logic of fashion" currently compels the following conclusion: Terror Porn is "hot."

John-Ivan Palmer ~ The Puppet Pushers

From NthPosition.com

John-Ivan Palmer is perspicacious and provocative, as usual, on the subject of tyrants and hypnotists:

More here

John-Ivan Palmer is perspicacious and provocative, as usual, on the subject of tyrants and hypnotists:

The path to our respective theaters of the absurd is the same - servility, seizure, sovereignty. Tyrants don't start off as terminal controllers and hypnotists do not "wake up one day" and discover they "have this power." They begin as failed magicians, birthday clowns, beauty shop operators, used car salesmen, welfare cases, who do what they have to do to become 'The World's Greatest', 'The World's Fastest', 'The Incredible', 'The Amazing', 'The Astounding." Terry Stokes, king of the West Coast hypnos, learned how to control people from a pimp. The hugely successful Pat Collins was such a bad lounge singer that someone told her as a cruel joke that she should become a hypnotist. So she did. In my case, I practiced from how-to books to get attention in bars.

Dictators don't start off with power either. They evolve, like hypnotists, from lower forms of life. A shyster lawyer, Jose Antonio Garcia Trevijano Fos, dean of the Faculty of Political Science and Economics at the University of Madrid, used Macías Nguema as a dummy front man for shady business deals in Equatorial Guinea. Which was fine until Nguema made that laughably incoherent speech at the United Nations, then went home and convinced everyone he could turn himself into a tiger and eat them. After that people did whatever he said, including the shyster lawyer. Idi Amin began as a servile comedy dog licking the fingers of his British military superiors. Thinking he was properly trained in obedience school he was manipulated into what the colonial powers assumed was subservient authority, at which point the fat pooch proceeded to throw a quarter million people to the crocodiles and call himself 'The Last King of Scotland'. Kim Il Sung began as such a weak-willed Sino-Soviet lackey that a Russian official flat out said, "We created him from zero." And Saddam Hussein went from neighborhood cat torturer to lowly rent-a-goon, then sucked up to the right people (before killing them). Eventually he billed himself as 'The Anointed One, The Glorious Leader, Direct Descendant of the Prophet, President of Iraq, Chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council, Field Marshall of its Armies, Doctor of its Laws, and Great Uncle to all its Peoples'. A bit much to fit on a business card, but if you're that anointed and glorious I suppose you don't need one.

At what point does the servility stop and the exaggerated influence begin? With hypnotists and tyrants alike there seems to be a turning point, a liminal event, a single performance after which the erstwhile loser experiences a profound and rapid inflation of power and ego. There's always that first show when you knew you really had them under. The Big Bang of the Absurd. For Saddam it was his 1979 inauguration. The liquidation stunt worked so well he could hardly believe it. For Jean-Bédel Bokassa it was the $25 million fantasy coronation he threw for himself on Napoleon's birthday, which no significant head of state attended. After that he became all at once, in his mind, "President For Life, Minister of Defense, Minister of Justice, Minister of Home Affairs, Minister of Agriculture, Minister of Health and Minister of Aviation." From then on it was said to be increasingly dangerous for anyone to contradict the crowned, bejeweled, ermine-draped, child-raping cannibal.

So too in every hypnotism show there's that precise point during the opening stunts, when its magical, irrational aspect crystallizes, and the back rows of the audience begin to stand up for a better look. An audience has no mind, only a collective urge for momentum, like one more hit off a strange addiction. The show, like the cult of Saddam or Kim Jong Il, then becomes its own autonomous, living entity. The fashions of trance behavior may have changed over the centuries, but one irreducible element has not - it's need to be convincing. And that comes by whatever means at whatever cost. I'll lie, I'll bribe, I'll threaten to make my show work. On stage I am The Anointed One and the spoils are mine.

Hypnotism is the riskiest of all novelty acts. Dictatorship is the riskiest of all political jobs. In both cases there's no allowance for failure. I've sat in audiences myself and watched beginning hypnotists struggle and fail to get people "under." I've seen them leave the stage in utter humiliation, ducking thrown pennies and a gauntlet of contempt like the twenty-two known plotters who tried to assassinate Idi Amin in the eight years of his reign. But for those who manage to achieve that initial strategic success, a further, more ominous transformation takes place.

The Amazing Rudolph began as little more than a playground wimp with high-water pants, a polyester tie and a bad haircut. He was easy to step on, both intentionally and by mistake. Once he was able to convince people they were walking through cow pies or surfboarding through a school of testicle-eating sharks, he took on (like his tyrannical counterparts) the air of someone with ultimate power. He became someone else. Instead of walking hunched over and fearful like some bully was about to yank up his underwear, he started to swagger. He wore flashy suits, pointy-toed boots, sported a pinkie ring and became cocky and obnoxious. He used every trick in the book to crush his competitors - including me - and drove to gigs in a muscle car, his head barely rising above the steering wheel.

One night in Las Vegas recently I experienced first-hand what it's like to be on the other side of the convincingness equation. I volunteered to be a participant in Justin Tranz's ninety-minute lounge show at Flamingo O'Shea's. As I followed his every command, I was completely aware of what I was doing. In fact, I was his best subject that night. I sang a rap song in Japanese, became the world's first pregnant man giving birth to a monkey, and played a saxophone with my buttocks. People were not laughing with me, they were laughing at me. I suppose I could have walked away at any time, but I didn't. Like Uday Hussein's body double, "I stopped worrying about whether what I was doing was useful or not. The longer I served the dictator, the more removed from reality I became." For me trance was the same response as that of Zainab Salbi, daughter of Saddam Hussein's personal pilot, "I just stepped into that painfully bright white space in my brain that had the power to burn [critical thought] away like overexposed film." With wielders of extreme control, surveillance is everything. As Salbi wrote of 'Uncle Saddam', he "knows how to read eyes." I wasn't worried about Mr Tranz drilling me with a power tool or nailing my ears to the wall, but the idea of getting up and leaving seemed out of the question. But I was conscious of his gaze upon me, monitoring my convincingness a thousand times a second - exactly what I do in my own show.

And as the vortex of absolute control swirls into the final flush, convincingness is no longer enough. Total soul-rooted devotion becomes the absolute requirement. A Vegas hypnotist back in the 70s wasn't above whispering to subjects off-mike, "Close 'em or I'll poke 'em out!" In caffeine-induced dreams I have maniacally clubbed fakers with my Shure SM58 wireless microphone, like President Bokasa personally beating to death with his cane those six kids who threw rocks at his motorcade. Castillo Gonzales, a linguist and expert on the Fang philosophical vocabulary in Equatorial Guinea was thought by Nguema to be one of those faking types. In prison he was beaten to death and his head cracked open to see if a faker's brain looked any different. Finding nothing of out of the ordinary, Professor Gonzales' brain was put to a more practical use. It was simply eaten by those present.

More here

How Phil K. Dick Took Over The World

From NthPosition.com

You don't expect eerily accurate prophecy from science fiction. It's especially weird when the work in question comes from the pen of Philip K Dick, a writer with no particular interest in science or the future. But somehow his 1965 novel The Zap Gun anticipates the modern world in a way that nobody else did.

Although people who never read it sometimes assume that it's trying to foretell the future, science fiction is rarely about predictions. More often it gives writers the chance to experimenting with ideas, writing in a realm that gives free rein to the imagination. Sometimes it's laziness. In SF, you can churn out thrillers without any knowledge of how the CIA operates, use detailed exotic locations without ever having been there, and write war stories without any need for historical accuracy. Iain M Banks refers to research as "the R word" and tries to avoid it as far as possible. SF writers can make up pretty much everything in their work, including the science.

In any case, imagined futures invariably look ridiculous long before their due date. Writers are stuck in their own present, and any work they produce will contain elements that look incongruous to later eras. Forties and Fifties SF is always funkily retro; when the space-age husband flies home his jet-car, he will still find his wife baking apple pie in the atomic oven, attended by stereotyped kids. Orwell's 1984, with its bombsites and pervasive smell of cabbage, is perfectly representative of post-war England. And don't even get me started on Star Trek and the Sixties.

Phil K Dick is beginning to be well-known because of film adaptations of his works. Blade Runner, Total Recall, Minority Report, the little-known Impostor and now A Scanner Darkly are all based on his stories. Hollywood likes to use them as pegs to hang action-adventures on, with shoot-outs and punch-ups for the likes of Arnie and Tom Cruise, but the originals have a very different style. Dick wrote ‘inner space' SF, concerned with issues like what it means to be human (Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, the basis of Blade Runner), whether you're the still same person if you lose your memory (Total Recall) , and whether it would be just to punish someone for what they will do in the future (Minority Report).

More here

You don't expect eerily accurate prophecy from science fiction. It's especially weird when the work in question comes from the pen of Philip K Dick, a writer with no particular interest in science or the future. But somehow his 1965 novel The Zap Gun anticipates the modern world in a way that nobody else did.

Although people who never read it sometimes assume that it's trying to foretell the future, science fiction is rarely about predictions. More often it gives writers the chance to experimenting with ideas, writing in a realm that gives free rein to the imagination. Sometimes it's laziness. In SF, you can churn out thrillers without any knowledge of how the CIA operates, use detailed exotic locations without ever having been there, and write war stories without any need for historical accuracy. Iain M Banks refers to research as "the R word" and tries to avoid it as far as possible. SF writers can make up pretty much everything in their work, including the science.

In any case, imagined futures invariably look ridiculous long before their due date. Writers are stuck in their own present, and any work they produce will contain elements that look incongruous to later eras. Forties and Fifties SF is always funkily retro; when the space-age husband flies home his jet-car, he will still find his wife baking apple pie in the atomic oven, attended by stereotyped kids. Orwell's 1984, with its bombsites and pervasive smell of cabbage, is perfectly representative of post-war England. And don't even get me started on Star Trek and the Sixties.

Phil K Dick is beginning to be well-known because of film adaptations of his works. Blade Runner, Total Recall, Minority Report, the little-known Impostor and now A Scanner Darkly are all based on his stories. Hollywood likes to use them as pegs to hang action-adventures on, with shoot-outs and punch-ups for the likes of Arnie and Tom Cruise, but the originals have a very different style. Dick wrote ‘inner space' SF, concerned with issues like what it means to be human (Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, the basis of Blade Runner), whether you're the still same person if you lose your memory (Total Recall) , and whether it would be just to punish someone for what they will do in the future (Minority Report).

More here

Thursday, September 21, 2006

Michael Rogers ~ What is the worth of words? Will it matter if people can't read in the future?

Michael Rogers thinks we're moving from a dislexic society to a post-lexic society. He's not alone.

From MSNBC.msn.com:

more here

From MSNBC.msn.com:

December 25, 2025 — Educational doomsayers are again up in arms at a new adult literacy study showing that less than 5 percent of college graduates can read a complex book and extrapolate from it.

The obsessive measurement of long-form literacy is once more being used to flail an education trend that is in fact going in just the right direction. Today’s young people are not able to read and understand long stretches of text simply because in most cases they won’t ever need to do so.

It’s time to acknowledge that in a truly multimedia environment of 2025, most Americans don’t need to understand more than a hundred or so words at a time, and certainly will never read anything approaching the length of an old-fashioned book. We need a frank reassessment of where long-form literacy itself lies in the spectrum of skills that a modern nation requires of its workers.

We’re not talking about complete illiteracy, which is most certainly not a good thing. Young people today, however, have plenty of literacy for everyday activities such as reading signs and package labels, and writing brief e-mails and text messages that don’t require accurate spelling or grammar.

Text labels also remain a useful way to navigate Web sites, although increasingly site design has evolved toward icons and audio prompts. Managers, in turn, have learned to use audio or video messaging as much as possible with workers, and to make sure that no text message ever contains more than one idea.

In 2025, when a worker actually needs to work with text, easy-to-use dictation, autoparsing and text-to-speech software allows him or her to create, edit and listen to documents without relying on extensive written skills. And any media analyst on Wall Street will confirm that the vast majority of Americans now consume virtually all of their entertainment and information through multimedia channels in which text is either optional or unnecessary.

In both the 19th and 20th centuries, the ability to read long texts was seen as an unquestioned social good. And back then, the prescription made sense: media technology was limited and in order to take part in both society and workplace, the ability to read books and long articles seemed essential. In 2025, higher-level literacy is probably necessary for only 10 percent of the American population.

more here

Thursday, September 14, 2006

A.S.Roma v Livorno 09.09.06

We jumped on the Metro to a place I forget, began with F. Flamini? From there, we got the No.2 Tram about four stops, and then we walk across the Tiber to the Olimpico. Jogging some of the way, as kick-off approaches. We go in Gate 25 and I get searched immediately. Momentarily, I have to remove my hat, my shades, and the scarf completely obscuring my face. It's all sweet though, naturally, so we make for the stairs, and as we rise to the top, the whole spectacle is right there in front of me. To the left, the infamous Curva Sud: ablaze with shoulder-to-shoulder showboating, as roman candles smoke, flags wave, and voices chant, blear and BANG! There's the loudest explosion I've ever heard, and the voice on the loudhailer is overpowered by the tannoy, as the teams are read out. With the eighth or ninth Roma player announced, the connection crackles, but the fans cheer their number all the same. Finally, it kicks back in, just in time for the custom call and answer...

Tannoy: "Francesco-" Fans: "Totti!"

We find our seats, and there's space around us, so I relax in half and take a couple of photographs that illustrate the look on Frankie's face perfectly: stunned. The teams walk out, and the drama is abetted by confetti, until they gather round the centre circle for a minute's applause for the late Giacinto Facchetti.

I'd say the first half was a non-event, but that would be bollocks. There wasn't much football played, but everything else was sensational. The Livorno fans, less than 200 in number in a stadium three quarters full of 50,000, start hurling objects at the Roma pack gathered in the Curva Nord. It looks like chaos, and it is, there's another explosion, and suddenly a fire - maybe from a petrol bomb - when the stewards surge, followed moments later by a Carabinieri charge. The hooligans retreat, the mood sours, but people start to settle down and get to grips wth the action.

Totti plays in the hole, but he's the last forward to track back. Simone Perotta and Di Rossi boss midfield, and I like the feet of the number 7. Livorno give as good as they get, and their right-winger is slickest of all; but the teams both look in early-season form, and my eyes rise to some glorious statue I can see through the roof of the stadium, high up on the hill to the West.

Boy dude with a coolbox appears, and I get a couple of beers and a cornetto. The noise level is insane, and it's unrelenting until the closing moments of the half. The Curva Sud leads the way, and there's a character about their song sheet, with vast and technical ditties intertwined with some curious hollering, whistling, and cat calling. Every now and then, with a misplaced pass or a thigh-high scythe, either a hundred jump on the referee's back or someone down the front thwacks their paper against their knee in frustration. It's all very emotional, and at this point I make a telephone call. Alas, I've no idea if I was heard because it was so much of an aural attack.

During the break, I start chatting to Leonardo in the next row. Three minutes later, he offers me something I shouldn't reveal on a public forum, and by the start of the second half, I'm chilled to the bone, with a fresh beer and a new voice in my ear. Roma play beautifully for a 15-minute spell, and Di Rossi scores a cracker from 25-yards out. There's lots of other excitement too, with some near misses, overhead kicks, and great dummies on show. Really, it was sophisticated football. There was even a naughty elbow.

Roma make the first of three subs, swapping number 7 for a lively right winger, and the new kid comes on and shoots with his first touch; the ball breaks and it's 2-0. In between, Totti missed a penalty, and all the time the rhythm from the stands is rah-rah-rah, while I'm now perched on the lip of my seat. Awestruck: every sense standing to atten-Z. Mancini, the Brasilian, who'd previously been disappointing, comes onto a game, and he devastates the left back with his trickery and pace. It could have been four, but we settle for coming back, and I'm delighted about that.

More explosions follow, and there's a beauty to proceedings, a sheer theatre, a dignity to the mayhem, ala gioco bello. Golazio: Amen.

Graeme Jamieson

Wednesday, September 06, 2006

Two Commercials by David Lynch

David Lynch unveiled his new movie, Inland Empire, at the Venice Film Festival this morning. Initial reports suggest this might be the American auteur's most uncompromising cinematic vision yet. Lynch held a press conference afterwards for an audience of, generally bemused, journalists. The Daily Telegraph correspondent's abiding impression of Lynch's 3 hour-long opus was the image of a rabbit ironing. Asked if he could explain the significance of this scene, Lynch replied, succinctly and somewhat impatiently, "No." A Norwegian's, almost equally asinine, response was to inquire if Mr. Lynch had been feeling well during the shoot. An mp3 of the conference can be found here

David Lynch unveiled his new movie, Inland Empire, at the Venice Film Festival this morning. Initial reports suggest this might be the American auteur's most uncompromising cinematic vision yet. Lynch held a press conference afterwards for an audience of, generally bemused, journalists. The Daily Telegraph correspondent's abiding impression of Lynch's 3 hour-long opus was the image of a rabbit ironing. Asked if he could explain the significance of this scene, Lynch replied, succinctly and somewhat impatiently, "No." A Norwegian's, almost equally asinine, response was to inquire if Mr. Lynch had been feeling well during the shoot. An mp3 of the conference can be found hereOn the subject of David Lynch; the maverick director has also directed a number of commercials over the years. I'm a self-confessed "commercia-phobe": I turn the sound off or change channels during advertising breaks. Commercials are the crack cocaine of our consumerist society and are as welcome in my household as ebola. Nevertheless, I can forgive Mr. Lynch for selling out to cretinous Commerce as no-one exchanges their soul for filthy lucre in a more aesthetically-arresting manner.

The first, from 1992, is a wonderfully stylish promo for a perfume by Georgio Armani. It can be found here

The second, from 1998, is a strange and surreal promo for Parissiene cigarettes. It can he found here

Both files are in quicktime format and are from Lynchnet.com

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)