After the vacuous designer-violence of Kill Bill (vols 1 & 2) and Sin City, it's both surprising and invigorating to discover a movie that takes violence seriously.

David Cronenberg has always been possessed of a singular artistic vision; Tarantino, by comparison, is merely a myopic medium channelling the superficial spirit of the zeitgeist. Tarantino's ultra-stylised sadism is as meaningful as MTV, and only marginally hipper. QT's cinematic output rarely amounts to more than the sum of the formulaic parts: killer soundtrack, fetishistic ultra-violence and a liberal sprinkling of pop-culture references. Tarantino sabotages his work with irony and, thus, divests it of meaning and distances himself from the realms of dreary consequentialism and artistic responsibility. Tarantino gives the public what he thinks they want: the pop-culture placebo. Cronenberg, by contrast, deals in uncut, unmediated expression.

For Tarantino, violence is the juice which powers his entire gas-guzzling, conspicuously-consuming, amoral oeuvre. Tarantino's ultra-violence is undermined by its ubiquity. In A History of Violence, Cronenberg uses violence economically and its potency resides not in the abstract aesthetic of its expression, but in the messy, morning-after, detritus of its after-effects and in its contagious capacity to corrupt and transform. Tarantino's violence is sexy, superficial and ubiquitous whereas Cronenberg's is nasty, brutish and short. Cronenberg dives into the deep end with Nietzsche, McLuhan, Kafka and Hobbes, but Quentin is content to cavort in the shallows with Bruce Lee, Giorgio Armani, Russ Meyer and Uma. Tarantino is dazzled by the glitterati but Cronenberg is more interested in the literati.

Cronenberg, the man who translated both Burroughs' and Ballard's "unfilmable" magna opera (Naked Lunch and Crash) into the cinematic medium, is undaunted by the challenge of integrating philosophy and cinema, high art and low culture. Like Burroughs, he uses pulp fiction as a vehicle to smuggle challenging, and often subversive, content into popular consciousness. If AHOV's subtext (that violence is a virus which infects, disfigures and diminishes us all) were any more Burroughsian it would be performing William Tell routines at parties.

A History of Violence opens with a daemonic, disturbing prologue: two dysfunctional drifters check out of a motel "with extreme prejudice." Cronenberg artfully misdirects our gaze from a mid-western My Lai-in-miniature. As the director distracts us with devilishly extraneous details, the murderers' disaffected, disconnected demeanours instantly contextualize their casual barbarity as the acts of desensitised veterans of violence.

In the following scene, a handsome father, Tom Stall (Viggo Mortensen), reassures his young daughter that monsters don't really exist. Of course, having just "witnessed" the motel massacre, we're already incapable of buying into this innocent worldview. As the film progresses, Daddy's reassuring fiction is, incrementally and terrifyingly, exposed as an elaborate deceit.

Tom Stall seems to be a soft-spoken, good-natured, pillar of Millbrook, Indiana's community. He lives in an idyllic farmhouse, runs the local diner, is married to a seriously sexy, successful, lawyer Edie (Maria Bello) and they have a couple of great kids (teenage son Jack and six-year-old Sarah). When Edie initiates hot sex by dressing up as the teenage cheerleader Tom wishes he'd met at high school, Cronenberg is telling us that life really couldn't be any better for Tom Stall, but he's already hinting that it may only be a pretence. The Apollonian abstraction of the movie's first sex scene is, later, contrasted with the Dionysian dynamic of a second, very different, encounter in which the "same" participants have been stripped of the dignifying, but deceitful, layers of assumed identity.

Cronenberg doesn't have to crank up the schmaltz quite so shamelessly as a Capra, or even a Lynch, for us to suspect that this idealised portrait of small-town, mid-western life is about to turn into Bad Day at Millbrook.

So when the evil drifters arrive at Stall's Diner, we're already prepared for a classic Western showdown between "good" and "evil", even if, as we suspect, Cronenberg is incapable of delineating such a simplistic dichotomy without smuggling a scintilla of post-modern mischief into the mix. When it comes, as we know it will, the violence is intense but ephemeral. Stall throws scalding coffee over one of his assailants, grabs his gun and kills them both. A lingering close-up of one of the corpses' bullet-ravaged craniums immediately sucks the air from the "small-town-hero" balloon, which is, invariably, inflated in such circumstances.

Stall's economical execution of the bad guys not only ensures that the subsequent question ("How come he's so good at killing people?") is entirely appropriate, but you wonder why it took

a) quite so long for anyone to get around to asking it

b) another out- of-town lowlife to finally state the obvious.

Seems like the entire community of Milbrook bought into Daddy's reassuringly innocent fiction.

The media's sycophantic treatment of Stall's, seemingly, heroic and proportionate response to aggression parallels its handling of the Bush administration's response to 9/11, but the ruthless efficiency underpinning Stall's self-defence attests to a history of violence lurking beneath the patina of heroism. Violence is encoded within Stall's (and America's) DNA.

Stall eschews the media's attentions with "man of few words" modesty. Canadian Cronenberg cunningly deconstructs Hollywood's heroic "all-American hero" archetype: Stall's laconic loner routine suggests he has something to hide.

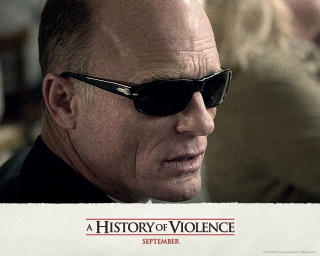

Tom and Edie want to return to the good old days but violence has, irrevocably, infected this family. The gift that just keeps on giving decants Philly mobster, Carl Fogarty (Ed Harris) and his two henchmen, out of a jet black Cadillac onto the Diner's doorstep. Fogarty orders coffee and, taking off his shades to reveal a badly scarred left eye, greets Tom as he would a long-lost acquaintance. Fogarty entertains no doubt that Tom Stall is really the guy who blinded him with barbed wire during a former incarnation as a ruthless Irish gangster, "Crazy" Joey Cusack -- "You're trying so hard to be this other guy, it's painful to watch." Tom's performance is so convincing at this point that we assume we've ventured into Hitchcockian "wrong man" territory, but our (and his own family's) doubts intensify as his façade of quiet confidence and amiable approachability soon shatters into a schizophrenic countenance betraying paranoia, fear and ruthlessness.

The residue from the initial "isolated" act of violence continues to metastasise and, before long, secondary acts are erupting and escalating, seemingly, exponentially: Tom's son Jack fights back against, and hospitalises, a high school bully; Tom chastises Jack for resorting to violence and, absurdly, punctuates his lecture with a blow; Tom and Edie act out a second, more aggressive, sex scene which contrasts sharply with the playfulness of the first; Jack graduates to murder (albeit in defence of his father) and "Crazy Joey" concludes the movie by committing carnage in Philadelphia (this last sequence, the penultimate scene of the film, features an over-the-top performance by William Hurt and improbable acts of carnage, which combine to unbalance the movie, but AHOV's absurd denouement is practically compelled by it's own, ever-escalating, arithmetic of violence).

After father and son eliminate Fogarty and his crew, "Tom" confesses to Edie, from his hospital bed, that, many years ago, he'd taken Joey out to the desert and "disposed" of him. From that day on he'd been Tom Stall. Edie throws up. The man she married was an impostor; her marriage a sham. Tom had effectively maintained this mild-mannered identity for nigh-on twenty years, but only "Crazy" Joey seems truly capable of protecting "his" family from the predations of Fogarty and his kind. Edie is both repelled by and attracted to the impostor and it is Joey who forces himself upon Edie in a brutal coupling on the stairs of the farmhouse. At first she fights back, but then appears to submit enthusiastically. It's debatable whether she's "really" responding to the remnants of romantic Tom or to the dominant and ruthless stranger, Joey.

The friendly local chief of police enquires, at one point, if, perhaps, Tom was in a witness protection programme. The film's recurring themes of reconstruction and reconfiguration of identity seem to imply that we're all part of a vast witness protection programme, that we're attempting to erase barely-sublimated memories of participation, or complicity, in primal violence and that our civilised lives are nothing more than fictional constructs which insulate and protect us from our own brutal, cruel, predatory natures.

The film closes upon Joey/Tom's return from Philadelphia. It's clear, as he takes his place at the head of the dinner table, that the "Stall" family aren't quite sure who has returned, or indeed who they are themselves any more, but it's equally clear that they'll make the necessary adjustments and that life will go on, if not quite as before, then at least, in something approximating to a passable facsimile of normality.

1 comment:

thank you, this is bang on, allways annoyed me artists that put their art as seperate and above life. To me it's very important that we are all one at some level, and so are all responsible for eachother and for our greatest 'mission' here: to do good. You are a wonderfull writer.

Post a Comment