Tuesday, December 05, 2006

War on Terror vs. Meek Acquiescence to Terror

Wednesday, November 15, 2006

David Lynch's Inland Empire

Christopher Walken ~ The Big Bad Wolf and the Three Little Pigs

Late one Saturday night in 1993, Christopher Walken made a brief appearance on British television. He came looming out of the darkness, seated in a huge cane chair, wearing an iridescent pink, yellow and green pullover, a giant book of fairy tales in his lap. “Hello, children,” he said in the monotone of a Bronx assassin. “Are you sitting comfortably?” And he started to read aloud from The Story of The Three Little Pigs. “In the village there was a wolf. A big wolf. Big bad wolf. Get the picture?” The story quickly heated up: “Exit pig one. Pig two, same story. ‘I’ll huff and I’ll puff and I’ll blow your house down.’ Arrividerci, porco numero due. Buon giorno, salami.” His performance was hilarious. Practically no-one has ever seen it.

Until now....

Christopher Walken's Three Little Pigs

Monday, October 16, 2006

Jedediah Palmer On Courtesy

From 3QuarksDaily

More hereCourtesy is a double-sided behavior, fully loaded with both positive and negative implication: It is forceful in its commission, and equally so in its absence. We communicate primitive dominance as well as refinement through the details of our behavior, and in this respect courtesy is little different from style of dress or vocal timbre. Allowing a door to close behind you is a message and a sentiment no less than is holding it open for the next person; in both cases you express yourself and your respect for those around you. In this sense, courtesy, or lack of it, is a weapon. That most basic of urban prohibitions, spitting, is a fine example of the conscious and violent absence of courtesy. Much as someone can direct his voice to indicate unmistakably its intended receiver, he can spit on the street and manage to communicate, through the intensity of expectoration and the relish with which it is committed, particular and specific contempt. An act of this kind should not be mistaken for anything other than a conscious gesture of discourtesy, just as expressive, if not more so, as its gentle flip-side. And in fact even positive acts of courtesy can be freighted with negative messages. Courteous behavior directed to three out of four people in a group is expressive not so much of respect for those three who received the benefit of the positive act, but of contempt for that fourth who was ignored. The insult is especially weighty when considered in the context of the group dynamic, where the awareness of the other three people involved maximizes the disrespect, both as it is communicated by the committer and as it is understood by the receiver.

Tuesday, October 10, 2006

The Departed

"I don't want to be a product of my environment. I want my environment to be a product of me."

"How's your mother?"

"On her way out."

"We all are. Act accordingly."

Sunday, October 01, 2006

Swingin' Sounds for Hipsters vol.3

It's subtitled Jet Set Jazz, Bossa, Boogaloo, Beatnik Beats & Funk Noir: The Fabulous Sounds of Now.

Thursday, September 28, 2006

Kurt Anderson ~ Hot for the Apocalpyse

The week of September 11 (two weeks ago, not five years), I noticed a poster up at Frankies, my sweet neighborhood trattoria in Brooklyn: It advertised a talk on 9/11 by Daniel Pinchbeck—the former downtown literary impresario who has become a Gen-X Carlos Castaneda and New Age impresario. My breakfast pal nodded at the poster and said, “The guy is selling his apocalypse thing hard.”

“Apocalypse thing?” I knew of Pinchbeck’s psychedelic enthusiasms, but I’d somehow missed his new book about the imminent epochal meltdown. In 2012, he interprets ancient Mayan prophecies to mean “our current socioeconomic system will suffer a drastic and irrevocable collapse” the year after next, and that in 2012, life as we know it will pretty much end. “We have to fix this situation right fucking now,” he said recently, “or there’s going to be nuclear wars and mass death … There’s not going to be a United States in five years, okay?”

The same day at lunch in Times Square, another friend happened to mention that he was thinking of buying a second country house—in Nova Scotia, as “a climate-change end-days hedge.” He smirked, but he was not joking.

On the subway home, I read the essay in the new Vanity Fair by the historian Niall Ferguson arguing that Europe and America in 2006 look disconcertingly like the Roman Empire of about 406—that is, the beginning of the end. That night, I began The Road, Cormac McCarthy’s new novel set in a transcendently bleak, apparently post-nuclear-war-ravaged America of the near future. And a day or so later watched the online trailer for Mel Gibson’s December movie, Apocalypto, set in the fifteenth-century twilight of, yes, the Mayan civilization.

So: Five years after Islamic apocalyptists turned the World Trade Center to fire and dust, we chatter more than ever about the clash of civilizations, fight a war prompted by our panic over (nonexistent) nuclear and biological weapons, hear it coolly asserted this past summer that World War III has begun, and wonder if an avian-flu pandemic poses more of a personal risk than climate change. In other words, apocalypse is on our minds. Apocalypse is … hot.

Millions of people—Christian millenarians, jihadists, psychedelicized Burning Men—are straight-out wishful about The End. Of course, we have the loons with us always; their sulfurous scent if not the scale of the present fanaticism is familiar from the last third of the last century—the Weathermen and Jim Jones and the Branch Davidians. But there seem to be more of them now by orders of magnitude (60-odd million “Left Behind” novels have been sold), and they’re out of the closet, networked, reaffirming their fantasies, proselytizing. Some thousands of Muslims are working seriously to provoke the blessed Armageddon. And the Christian Rapturists’ support of a militant Israel isn’t driven mainly by principled devotion to an outpost of Western democracy but by their fervent wish to see crazy biblical fantasies realized ASAP—that is, the persecution of the Jews by the Antichrist and the Battle of Armageddon.

When apocalypse preoccupations leach into less-fantastical thought and conversation, it becomes still more disconcerting. Even among people sincerely fearful of climate change or a nuclearized Iran enacting a “second Holocaust” by attacking Israel, one sometimes detects a frisson of smug or hysterical pleasure.

As in the excited anticipatory chatter about Iran’s putative plans to fire a nuke on the 22nd of last month—in order to provoke apocalypse and pave the way for the return of the Shiite messiah, a miracle in which President Ahmadinejad apparently believes. Princeton’s Bernard Lewis, at 90 still the preeminent historian of Islam, published a piece in The Wall Street Journal to spread this false alarm.

And as in Charles Krauthammer’s column the other day: He explained how a U.S. military attack on Iran would double the price of oil, ruin the global economy, redouble hatred for America, and incite terrorism worldwide—but that we had to go for it anyway because of “the larger danger of permitting nuclear weapons to be acquired by religious fanatics seized with an eschatological belief in the imminent apocalypse and in their own divine duty to hasten the End of Days.” In other words: Ratchet up the risk of Armageddon sooner in order to prevent a possible Armageddon later.

I worry that such fast-and-loose talk, so ubiquitous and in so many flavors, might in the aggregate be greasing the skids, making the unthinkable too thinkable, turning us all a little Dr. Strangelovian, actually increasing the chance—by a little? A lot? Lord knows—that doomsday prophecies will become self-fulfilling. It’s giving me the heebie-jeebies.

More here

Monday, September 25, 2006

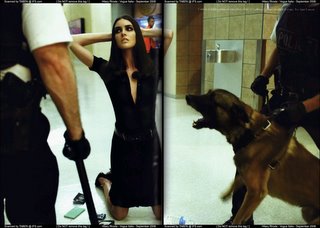

The Atrocity Exhibition, the Death of Affect, Vogue Italia and Terror Porn

Terror has become a self-replicating media virus. Al-Qa'ida snuff movies inspire imitative acts of barbarism. It's hardly surprising that the sadism of Abu Ghraib has been appropriated by terminal hipsters hard-wired into the Apocalyptic Zeitgeist. This month's Vogue Italia testifies to this rapidly-metastasising culture of cruelty. It features an, ostensibly, incendiary photoshoot from Steven Meisel. State of Emergency recycles, at least one of, the truly shocking images from Abu Ghraib (themselves "inspired" by violent pornography) into fashionably fetishistic soft core porn that both trivialises terror and de-sexes sex. Stark sadism eviscerated, re-configured and re-branded as a slick, hyper-sexualised advertising campaign featuring emaciated models subjected to imagined ordeals at the hands of faux-sadists. As Mark Fisher (k-punk) observes at Ballardian.com: "The overt sexualisation and compulsory carnality of postmodern image culture distracts us from the essential staidness of its rendition of the erotic." In our celebrity-obsessed, consumer culture the "banalification" of evil is, seemingly, endemic. Atrocity rendered anodyne. "The atrocities of September 11th and Abu Ghraib mimetised in the alternate death of Paris Hilton."

Meisel's photos can be found here.

Synchronously, I'm re-reading J.G. Ballard's perversely prescient and prophetic 1960s' novel, The Atrocity Exhibition right now:

Dr. Nathan gestured at the war newsreels transmitted from the television set. Catherine Austin watched from the radiator panel, arms folded across her beasts. "Any great human tragedy - Vietnam, let us say - can be considered experimentally as a larger model of a mental crisis mimetized in faulty stair angles or skin junctions, breakdowns in the perceptions of environments and consciousness. In terms of television and the news magazines, the war in Vietnam has a latent significance very different from its manifest content. Far from repelling us, it appeals to us by virtue of its complex of polyperverse acts. We must bear in mind, however sadly, that psychopathology is no longer the exclusive preserve of the degenerate and the perverse. The Congo, Vietnam, Biafra - these are games that anyone can play. Their violence, and all violence for that matter, reflects the neutral exploration of sensation that is taking place now, within sex as elsewhere, and the sense that the perversions are valuable precisely because they provide a readily accessible anthology of exploratory techniques. Where all this leads one can only speculate....

Sex, of course, remains our continuing preoccupation. As you and I know, the act of intercourse is now always a model for something else. What will follow is the psychopathology of sex, relations so lunar and abstract that people will become mere extensions of the geometries of situations. This will allow for exploration, without any trace of guilt, of every aspect of sexual psychopathology. Travers, for example, has composed a series of new sexual deviations, of a wholly conceptual character, in an attempt to surmount this death of affect. In many ways he is the first of the new naives, a Douanier Rousseau of the sexual perversions. However consoling, it seems likely that our familiar perversions will soon come to an end, if only because their equivalents are too readily available in strange stair angles, in the mysterious eroticism of overpasses, in distortions of gesture and posture. At the logic of fashion, such once-popular perversions as paedophilia, and sodomy, will become derided clichés, as amusing as pottery ducks on suburban walls."

The "logic of fashion" currently compels the following conclusion: Terror Porn is "hot."

John-Ivan Palmer ~ The Puppet Pushers

John-Ivan Palmer is perspicacious and provocative, as usual, on the subject of tyrants and hypnotists:

The path to our respective theaters of the absurd is the same - servility, seizure, sovereignty. Tyrants don't start off as terminal controllers and hypnotists do not "wake up one day" and discover they "have this power." They begin as failed magicians, birthday clowns, beauty shop operators, used car salesmen, welfare cases, who do what they have to do to become 'The World's Greatest', 'The World's Fastest', 'The Incredible', 'The Amazing', 'The Astounding." Terry Stokes, king of the West Coast hypnos, learned how to control people from a pimp. The hugely successful Pat Collins was such a bad lounge singer that someone told her as a cruel joke that she should become a hypnotist. So she did. In my case, I practiced from how-to books to get attention in bars.

Dictators don't start off with power either. They evolve, like hypnotists, from lower forms of life. A shyster lawyer, Jose Antonio Garcia Trevijano Fos, dean of the Faculty of Political Science and Economics at the University of Madrid, used Macías Nguema as a dummy front man for shady business deals in Equatorial Guinea. Which was fine until Nguema made that laughably incoherent speech at the United Nations, then went home and convinced everyone he could turn himself into a tiger and eat them. After that people did whatever he said, including the shyster lawyer. Idi Amin began as a servile comedy dog licking the fingers of his British military superiors. Thinking he was properly trained in obedience school he was manipulated into what the colonial powers assumed was subservient authority, at which point the fat pooch proceeded to throw a quarter million people to the crocodiles and call himself 'The Last King of Scotland'. Kim Il Sung began as such a weak-willed Sino-Soviet lackey that a Russian official flat out said, "We created him from zero." And Saddam Hussein went from neighborhood cat torturer to lowly rent-a-goon, then sucked up to the right people (before killing them). Eventually he billed himself as 'The Anointed One, The Glorious Leader, Direct Descendant of the Prophet, President of Iraq, Chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council, Field Marshall of its Armies, Doctor of its Laws, and Great Uncle to all its Peoples'. A bit much to fit on a business card, but if you're that anointed and glorious I suppose you don't need one.

At what point does the servility stop and the exaggerated influence begin? With hypnotists and tyrants alike there seems to be a turning point, a liminal event, a single performance after which the erstwhile loser experiences a profound and rapid inflation of power and ego. There's always that first show when you knew you really had them under. The Big Bang of the Absurd. For Saddam it was his 1979 inauguration. The liquidation stunt worked so well he could hardly believe it. For Jean-Bédel Bokassa it was the $25 million fantasy coronation he threw for himself on Napoleon's birthday, which no significant head of state attended. After that he became all at once, in his mind, "President For Life, Minister of Defense, Minister of Justice, Minister of Home Affairs, Minister of Agriculture, Minister of Health and Minister of Aviation." From then on it was said to be increasingly dangerous for anyone to contradict the crowned, bejeweled, ermine-draped, child-raping cannibal.

So too in every hypnotism show there's that precise point during the opening stunts, when its magical, irrational aspect crystallizes, and the back rows of the audience begin to stand up for a better look. An audience has no mind, only a collective urge for momentum, like one more hit off a strange addiction. The show, like the cult of Saddam or Kim Jong Il, then becomes its own autonomous, living entity. The fashions of trance behavior may have changed over the centuries, but one irreducible element has not - it's need to be convincing. And that comes by whatever means at whatever cost. I'll lie, I'll bribe, I'll threaten to make my show work. On stage I am The Anointed One and the spoils are mine.

Hypnotism is the riskiest of all novelty acts. Dictatorship is the riskiest of all political jobs. In both cases there's no allowance for failure. I've sat in audiences myself and watched beginning hypnotists struggle and fail to get people "under." I've seen them leave the stage in utter humiliation, ducking thrown pennies and a gauntlet of contempt like the twenty-two known plotters who tried to assassinate Idi Amin in the eight years of his reign. But for those who manage to achieve that initial strategic success, a further, more ominous transformation takes place.

The Amazing Rudolph began as little more than a playground wimp with high-water pants, a polyester tie and a bad haircut. He was easy to step on, both intentionally and by mistake. Once he was able to convince people they were walking through cow pies or surfboarding through a school of testicle-eating sharks, he took on (like his tyrannical counterparts) the air of someone with ultimate power. He became someone else. Instead of walking hunched over and fearful like some bully was about to yank up his underwear, he started to swagger. He wore flashy suits, pointy-toed boots, sported a pinkie ring and became cocky and obnoxious. He used every trick in the book to crush his competitors - including me - and drove to gigs in a muscle car, his head barely rising above the steering wheel.

One night in Las Vegas recently I experienced first-hand what it's like to be on the other side of the convincingness equation. I volunteered to be a participant in Justin Tranz's ninety-minute lounge show at Flamingo O'Shea's. As I followed his every command, I was completely aware of what I was doing. In fact, I was his best subject that night. I sang a rap song in Japanese, became the world's first pregnant man giving birth to a monkey, and played a saxophone with my buttocks. People were not laughing with me, they were laughing at me. I suppose I could have walked away at any time, but I didn't. Like Uday Hussein's body double, "I stopped worrying about whether what I was doing was useful or not. The longer I served the dictator, the more removed from reality I became." For me trance was the same response as that of Zainab Salbi, daughter of Saddam Hussein's personal pilot, "I just stepped into that painfully bright white space in my brain that had the power to burn [critical thought] away like overexposed film." With wielders of extreme control, surveillance is everything. As Salbi wrote of 'Uncle Saddam', he "knows how to read eyes." I wasn't worried about Mr Tranz drilling me with a power tool or nailing my ears to the wall, but the idea of getting up and leaving seemed out of the question. But I was conscious of his gaze upon me, monitoring my convincingness a thousand times a second - exactly what I do in my own show.

And as the vortex of absolute control swirls into the final flush, convincingness is no longer enough. Total soul-rooted devotion becomes the absolute requirement. A Vegas hypnotist back in the 70s wasn't above whispering to subjects off-mike, "Close 'em or I'll poke 'em out!" In caffeine-induced dreams I have maniacally clubbed fakers with my Shure SM58 wireless microphone, like President Bokasa personally beating to death with his cane those six kids who threw rocks at his motorcade. Castillo Gonzales, a linguist and expert on the Fang philosophical vocabulary in Equatorial Guinea was thought by Nguema to be one of those faking types. In prison he was beaten to death and his head cracked open to see if a faker's brain looked any different. Finding nothing of out of the ordinary, Professor Gonzales' brain was put to a more practical use. It was simply eaten by those present.

More here

How Phil K. Dick Took Over The World

You don't expect eerily accurate prophecy from science fiction. It's especially weird when the work in question comes from the pen of Philip K Dick, a writer with no particular interest in science or the future. But somehow his 1965 novel The Zap Gun anticipates the modern world in a way that nobody else did.

Although people who never read it sometimes assume that it's trying to foretell the future, science fiction is rarely about predictions. More often it gives writers the chance to experimenting with ideas, writing in a realm that gives free rein to the imagination. Sometimes it's laziness. In SF, you can churn out thrillers without any knowledge of how the CIA operates, use detailed exotic locations without ever having been there, and write war stories without any need for historical accuracy. Iain M Banks refers to research as "the R word" and tries to avoid it as far as possible. SF writers can make up pretty much everything in their work, including the science.

In any case, imagined futures invariably look ridiculous long before their due date. Writers are stuck in their own present, and any work they produce will contain elements that look incongruous to later eras. Forties and Fifties SF is always funkily retro; when the space-age husband flies home his jet-car, he will still find his wife baking apple pie in the atomic oven, attended by stereotyped kids. Orwell's 1984, with its bombsites and pervasive smell of cabbage, is perfectly representative of post-war England. And don't even get me started on Star Trek and the Sixties.

Phil K Dick is beginning to be well-known because of film adaptations of his works. Blade Runner, Total Recall, Minority Report, the little-known Impostor and now A Scanner Darkly are all based on his stories. Hollywood likes to use them as pegs to hang action-adventures on, with shoot-outs and punch-ups for the likes of Arnie and Tom Cruise, but the originals have a very different style. Dick wrote ‘inner space' SF, concerned with issues like what it means to be human (Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, the basis of Blade Runner), whether you're the still same person if you lose your memory (Total Recall) , and whether it would be just to punish someone for what they will do in the future (Minority Report).

More here

Thursday, September 21, 2006

Michael Rogers ~ What is the worth of words? Will it matter if people can't read in the future?

From MSNBC.msn.com:

December 25, 2025 — Educational doomsayers are again up in arms at a new adult literacy study showing that less than 5 percent of college graduates can read a complex book and extrapolate from it.

The obsessive measurement of long-form literacy is once more being used to flail an education trend that is in fact going in just the right direction. Today’s young people are not able to read and understand long stretches of text simply because in most cases they won’t ever need to do so.

It’s time to acknowledge that in a truly multimedia environment of 2025, most Americans don’t need to understand more than a hundred or so words at a time, and certainly will never read anything approaching the length of an old-fashioned book. We need a frank reassessment of where long-form literacy itself lies in the spectrum of skills that a modern nation requires of its workers.

We’re not talking about complete illiteracy, which is most certainly not a good thing. Young people today, however, have plenty of literacy for everyday activities such as reading signs and package labels, and writing brief e-mails and text messages that don’t require accurate spelling or grammar.

Text labels also remain a useful way to navigate Web sites, although increasingly site design has evolved toward icons and audio prompts. Managers, in turn, have learned to use audio or video messaging as much as possible with workers, and to make sure that no text message ever contains more than one idea.

In 2025, when a worker actually needs to work with text, easy-to-use dictation, autoparsing and text-to-speech software allows him or her to create, edit and listen to documents without relying on extensive written skills. And any media analyst on Wall Street will confirm that the vast majority of Americans now consume virtually all of their entertainment and information through multimedia channels in which text is either optional or unnecessary.

In both the 19th and 20th centuries, the ability to read long texts was seen as an unquestioned social good. And back then, the prescription made sense: media technology was limited and in order to take part in both society and workplace, the ability to read books and long articles seemed essential. In 2025, higher-level literacy is probably necessary for only 10 percent of the American population.

more here

Thursday, September 14, 2006

A.S.Roma v Livorno 09.09.06

We jumped on the Metro to a place I forget, began with F. Flamini? From there, we got the No.2 Tram about four stops, and then we walk across the Tiber to the Olimpico. Jogging some of the way, as kick-off approaches. We go in Gate 25 and I get searched immediately. Momentarily, I have to remove my hat, my shades, and the scarf completely obscuring my face. It's all sweet though, naturally, so we make for the stairs, and as we rise to the top, the whole spectacle is right there in front of me. To the left, the infamous Curva Sud: ablaze with shoulder-to-shoulder showboating, as roman candles smoke, flags wave, and voices chant, blear and BANG! There's the loudest explosion I've ever heard, and the voice on the loudhailer is overpowered by the tannoy, as the teams are read out. With the eighth or ninth Roma player announced, the connection crackles, but the fans cheer their number all the same. Finally, it kicks back in, just in time for the custom call and answer...

Tannoy: "Francesco-" Fans: "Totti!"

We find our seats, and there's space around us, so I relax in half and take a couple of photographs that illustrate the look on Frankie's face perfectly: stunned. The teams walk out, and the drama is abetted by confetti, until they gather round the centre circle for a minute's applause for the late Giacinto Facchetti.

I'd say the first half was a non-event, but that would be bollocks. There wasn't much football played, but everything else was sensational. The Livorno fans, less than 200 in number in a stadium three quarters full of 50,000, start hurling objects at the Roma pack gathered in the Curva Nord. It looks like chaos, and it is, there's another explosion, and suddenly a fire - maybe from a petrol bomb - when the stewards surge, followed moments later by a Carabinieri charge. The hooligans retreat, the mood sours, but people start to settle down and get to grips wth the action.

Totti plays in the hole, but he's the last forward to track back. Simone Perotta and Di Rossi boss midfield, and I like the feet of the number 7. Livorno give as good as they get, and their right-winger is slickest of all; but the teams both look in early-season form, and my eyes rise to some glorious statue I can see through the roof of the stadium, high up on the hill to the West.

Boy dude with a coolbox appears, and I get a couple of beers and a cornetto. The noise level is insane, and it's unrelenting until the closing moments of the half. The Curva Sud leads the way, and there's a character about their song sheet, with vast and technical ditties intertwined with some curious hollering, whistling, and cat calling. Every now and then, with a misplaced pass or a thigh-high scythe, either a hundred jump on the referee's back or someone down the front thwacks their paper against their knee in frustration. It's all very emotional, and at this point I make a telephone call. Alas, I've no idea if I was heard because it was so much of an aural attack.

During the break, I start chatting to Leonardo in the next row. Three minutes later, he offers me something I shouldn't reveal on a public forum, and by the start of the second half, I'm chilled to the bone, with a fresh beer and a new voice in my ear. Roma play beautifully for a 15-minute spell, and Di Rossi scores a cracker from 25-yards out. There's lots of other excitement too, with some near misses, overhead kicks, and great dummies on show. Really, it was sophisticated football. There was even a naughty elbow.

Roma make the first of three subs, swapping number 7 for a lively right winger, and the new kid comes on and shoots with his first touch; the ball breaks and it's 2-0. In between, Totti missed a penalty, and all the time the rhythm from the stands is rah-rah-rah, while I'm now perched on the lip of my seat. Awestruck: every sense standing to atten-Z. Mancini, the Brasilian, who'd previously been disappointing, comes onto a game, and he devastates the left back with his trickery and pace. It could have been four, but we settle for coming back, and I'm delighted about that.

More explosions follow, and there's a beauty to proceedings, a sheer theatre, a dignity to the mayhem, ala gioco bello. Golazio: Amen.

Graeme Jamieson

Wednesday, September 06, 2006

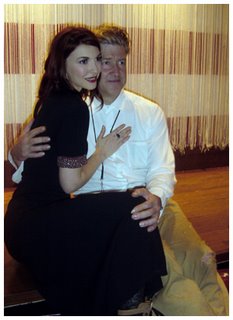

Two Commercials by David Lynch

David Lynch unveiled his new movie, Inland Empire, at the Venice Film Festival this morning. Initial reports suggest this might be the American auteur's most uncompromising cinematic vision yet. Lynch held a press conference afterwards for an audience of, generally bemused, journalists. The Daily Telegraph correspondent's abiding impression of Lynch's 3 hour-long opus was the image of a rabbit ironing. Asked if he could explain the significance of this scene, Lynch replied, succinctly and somewhat impatiently, "No." A Norwegian's, almost equally asinine, response was to inquire if Mr. Lynch had been feeling well during the shoot. An mp3 of the conference can be found here

David Lynch unveiled his new movie, Inland Empire, at the Venice Film Festival this morning. Initial reports suggest this might be the American auteur's most uncompromising cinematic vision yet. Lynch held a press conference afterwards for an audience of, generally bemused, journalists. The Daily Telegraph correspondent's abiding impression of Lynch's 3 hour-long opus was the image of a rabbit ironing. Asked if he could explain the significance of this scene, Lynch replied, succinctly and somewhat impatiently, "No." A Norwegian's, almost equally asinine, response was to inquire if Mr. Lynch had been feeling well during the shoot. An mp3 of the conference can be found hereOn the subject of David Lynch; the maverick director has also directed a number of commercials over the years. I'm a self-confessed "commercia-phobe": I turn the sound off or change channels during advertising breaks. Commercials are the crack cocaine of our consumerist society and are as welcome in my household as ebola. Nevertheless, I can forgive Mr. Lynch for selling out to cretinous Commerce as no-one exchanges their soul for filthy lucre in a more aesthetically-arresting manner.

The first, from 1992, is a wonderfully stylish promo for a perfume by Georgio Armani. It can be found here

The second, from 1998, is a strange and surreal promo for Parissiene cigarettes. It can he found here

Both files are in quicktime format and are from Lynchnet.com

Thursday, August 10, 2006

Apocalypse a Week on Tuesday, Weather Permitting

At first the news networks seemed to convey the impression that up to 50 terrorists had been restrained from boarding planes bound for USA yesterday morning, intent on blowing them out of the sky. Reflecting this sense of imminent threat, this morning's edition of "The Independent"' ran with a front page boldy proclaiming: "10/8, Was This Going to be the Next Date in the Calendar of Terror?"

However, as yesterday progressed, US Homeland Security Secretary, Michael Chertoff informed us that the terrorists weren't ready to go after all, but were merely "getting close to execution phase." "They were not yet sitting on an airplane," but were close to travelling, a senior U.S. counterterrorism official told The Associated Press. Before long, we were getting the impression the terrorists had lost their passports down the back of Condoleezza Rice's couch and, sure enough, Homeland Security were soon speculating that we may have been as "close" as two days away from a "rehearsal" and that the real thing might well have followed "a few days after that". From "Apocalypse Now" to "Apocalypse a Week on Tuesday, Weather Permitting."

Not only that, but early-morning emphasis on the the triumphant anti-terrorist activities of UK intelligence agencies and police forces became diluted, mid-afternoon, by increasingly influential US intervention. Predictably, Bush couldn't be restrained fom crowing about the inexorably-accelerating Islamo-fascist threat and the algebraically-escalating urgency of waging unrestrained war on terror.

By the end of the day it was all about the US: Bush was practically claiming proprietorial rights to a "terrorist plot aimed at US airlines and US cities." He was also, reassuringly, promising to send many more armed US air marshals to patrol our airports and "safeguard" our flights. We can probably interpret this as fair warning that we're on the cusp of being designated, like Lebanon, as a state harbouring terrorist organisations inimical to US interests. Who knows, we might eventually become eligible for fully-fledged "Axis of Evil" status? Future "targeted" bombing raids aimed at destroying our indigenous terror networks (with "minimal" collateral civilian damage) must, logically, follow.

It's hard to deconstruct the news right now. The truth is, presumably, hiding beneath the veneer of propaganda, but it feels like we're in the middle of a "long con." There's a multi-dimensional strategy unfolding, that's for sure. With this much misdirection going on, there's just got to be a con ~ and we already know we're the suckers. Blair's fawning "relationship" with Bush reminds me of a naïve ingenue with a crush on a movie star. Don't play victim when it all goes wrong, Tone. If you get into bed with Warren Beatty, you know you're going to get fucked.

Wednesday, August 09, 2006

Stanley Crouch ~ MTV, still clueless after all these years

Last week, MTV celebrated its 25th anniversary, marking a quarter of a century after having conceived of the first actually new thing in popular television entertainment since "American Bandstand" and "Soul Train."

The music video became a big deal through MTV and not only updated the old "soundies" once shown in movie theaters to feature singers and instrumentalists. It also revolutionized the making of films by acclimating its audience to the extremely fast crosscutting that had been pioneered in television commercials, where the faster the message arrived, the better. In the process, the MTV audience learned to see much more quickly and recognize what sometimes quite surreal montages were saying or what they were alluding to - no small accomplishment.

Of course, that is not the whole story of MTV, which also came to project the most dehumanizing images of black people since the dawn of minstrelsy in the 19th century. Pimps, whores, potheads, dope dealers, gangbangers, the crudest materialism and anarchic gang violence were broadcast around the world as "real" black culture.

At first, far too many black people were taken in by the cult of celebrity and the wealth that came to these gold- toothed knuckleheads and mindless hussies to realize what was happening. The lowest possible common denominator was seen as the norm. The illiteracy and rule-of-thumb stupidity was interpreted as a "cultural" rejection of white middle-class norms.

It was as if these dregs had the same heroic position in our time as the largely uneducated Southern black poor of the civil rights movement. Those Southern black people, like the marvelous Fannie Lou Hamer, proved to this nation and to the world that they not only deserved their constitutional rights, but had something both noble and soulful to add to our American understanding of the richness of the human spirit. We are a much greater nation because of the success of the civil rights movement. As they emerged from beneath the bloody rock of segregation, those Southern black people brought to our national identity a compassion and a bravery of immeasurable value.

Unfortunately, the crabbed thug culture that was popularized through MTV brought nothing big with it other than some paychecks.

More here

Tuesday, August 01, 2006

Tone's "Alliance of Moderation" Recruits Piano Player

If the "Yo, Blair" episode didn't tell us all we needed to know about the nature of your "special relationship" with Dubya, Tone, the fact that Arnie "I'll be back" Schwarzenegger is the only politician on the other side of the pond prepared to talk to you about climate change, tells us the rest. It seems our PM has eschewed any pretence of statesmanship in favour of hangin' with Snoop Dogg in L.A.'s Sky Bar as Lebanon burns. "Yo, Tone! How does it feel to be Bush's bitch?"

Perhaps Blair was referring to the composition of the international peacekeeping force earmarked for southern Lebanon? If we're going to throw some nice Christians into the buffer zone between the Islamic and Israeli lions, then let's make sure we get the right guys and gals for the job. What good would an "Alliance of Moderation" be without Harry Connick Jnr? We need a piano player; that's a given, and the Vice-Chairman of the Board's gotta be the first name on the list. Laura Dern, she's a sweet girl. A hottie for Hezbollah in exchange for the Israeli hostages? Jim Carrey would be a wild card, a joker to undermine the jihad.

I reckon Tom Cruise and Katie Holmes could solve this dispute on their own. What South Lebanon needs now is Scientology. Hubba-Hubba, Hezbollah, it's Katyusha Katie and the Cruise Missile! Do the El Ron Ron, the El Ron Ron.

Swingin' Sounds for Hipsters vol. 2

Thursday, July 20, 2006

Wednesday, July 19, 2006

Health, Safety and the Hitman

When a Brazilian electrician, with as much connection to al-Qā'idah/international terror as Celine Dion, gets snuffed "Mafia-style" on the floor of a tube train (by armed police officers injecting seven shots of hot lead directly into his cerebellum), "concern and disappointment" follow as inexorably as death and taxes. On second thoughts, I'm doing Cosa Nostra a disservice here: they're, invariably, more humane and more economical with the ammunition.

"Concern and disappointment", suitably eviscerated almost-emotions, strike me as wholly consistent with, and proportionate to, the Crown Prosecution's micro-response to this tragedy.

I agree with The Independent's Mark Steel. The CPS's decision to recategorise and trivialise this tragic incident as a "health and safety" issue is absurd. The Health and Safety Executive would doubtless insist that, when executing an innocent man with extreme prejudice, the police should avoid discharging loud weapons if not wearing ear muffs. "Because regularly shooting people without adequate ear protection could lead in later life to tinnitus, or even in severe cases partial deafness. "

Wednesday, July 12, 2006

Chrysta Bell/David Lynch, Ersatz Empire, Kristen Kerr & The Doppelganger Dahlia

According to David Lynch's friend and collaborator, John Neff, over at Twin Peaks Gazette, the long-anticipated (well, here at casa del ionesco at any rate) Chrysta Bell/David Lynch/John Neff musical, and associated video, projects are now unlikely to see the light of day:

Well, Dave and I did three songs that Chrysta came in and sang on (Does that make them 'hers'?). We shot videos of them at a club where we did a scene from "Inland Empire". Some of it was supposed to be in the movie, I guess, I never got a definitive answer. We were supposed to finish a CD project with her last year, but it never happened. The videos were supposed to go to some media outlet, I never heard which if any had been contacted. The songs were supposed to be released to iTunes this year, as well as some Rebekah Del Rio stuff that we did. When the contract arrived it was horrendous and was rejected. I have only heard from his attorney that the releases have been cancelled and I believe they will not be in the film either. I have also heard that she is recording new stuff with David that I am not a part of. This is all I know.

The club where Lynch shot the Chrysta Bell videos, and one of the scenes for his upcoming movie, Inland Empire, was L.A. burlesque joint Forty Deuce.

One of the songs which Lynch, Neff and Bell collaborated on, has finally shown up in the following scene, taken from a DVD called Room To Dream, which showcases Digital Video (Lynch's chosen delivery medium for Inland Empire) as an affordable and user-friendly option for aspiring auteurs. Sadly, the divine Bell is absent, though, like the bizarre male character in this scene (and The Mystery Man in Lost Highway), she's simultaneously absent and present: her ethereal vocals are replaced by the rather more earth-bound vocal stylings of the almost equally beautiful Chrysta Bell doppelganger, Kristin Kerr, Stanley Kamel & the other, relatively unremarkable, actress who appears in the scene.

Kamel and Kerr both feature in Inland Empire's cast, and it is thought that this scene is an excerpt ~ or a reworking, or a rough draft, of a scene ~ from that movie. Of course, it may be an entirely unconnected scene, shot exclusively for the "R2D" DVD during a break in the Inland Empire shoot, but John Neff's enigmatic posts on the Twin Peaks Gazette forum seem to substantiate the former theory.

Ersatz Empire ?

Kristen Kerr, in a Lynch-esque identity twist, is also due to star in an alternate version of James Ellroy's Black Dahlia story, due to be released almost simulataneously with the Brian De Palma version. In the doppelganger "Dahlia", Kerr plays two different characters (Lisa Small and Elizabeth Short) and is one of two actresses to portay Short (the other, Lizzy Strain, also "plays" herself). Sounds almost convoluted enough to be the plotline to Lynch's Mulholland Dr.

Monday, July 10, 2006

David Lynch's Inland Empire for Venice Film Festival

David Lynch's Inland Empire, starring Laura Dern, Justin Theroux, Harry Dean Stanton and Jeremy Irons, is scheduled to appear, though not compete, at the 63rd Venice International Film Festival, which runs from August 30th until September 9th. Lynch will receive the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement award at the festival.

Brian De Palma's adaption of James Ellroy's The Black Dahlia is also scheduled to appear.

Wednesday, July 05, 2006

Cult of Impersonality

Fame is fleeting, but to Samuel Beckett's taste, not fleeting enough. If most writers feel themselves condemned to obscurity, for Beckett the opposite was the case. He was, in his own words, ``damned to fame."

Indeed, the durability of his fame is on striking display these days. In celebration of Beckett's centennial, his plays are being produced in hundreds of theaters around the world; conferences and colloquia are taking place everywhere from Dublin to Oxford, Paris to Tokyo, Ankara to Odense; and a splendid new edition of his works, edited by Paul Auster (and with introductions by Colm Toibin, Salman Rushdie, Edward Albee, and J.M. Coetzee), has just been published by Grove Press.

Beckett, who died in 1989, lived to see the full flowering of his fame, and the retiring Irishman was forced into a spotlight he had no desire to stand in. But what were the chances that this spotlight would shine on him in the first place? He was an obscure writer writing in a foreign language about obscure figures living in a very foreign world. When one considers the strangeness of the works that sealed his fame, the plays ``Waiting for Godot" and ``Endgame," both written in the 1950s, not only is it remarkable that they were successes, it is remarkable that they were produced-and that the first audiences were patient enough to await their seemingly endless endings. But wait they did. And to his limitless consternation, Samuel Beckett became an international literary celebrity.

With piercing blue eyes, a gaunt face scored by lines of laughter and loss, and hair standing on end-as if outraged by the thoughts transpiring beneath it-Beckett looked the part, and got the part. And thanks to the special logic of fame, the more he tried to lead a private life, the more he tried to move away from literary groups, associations, councils, and societies, the more they courted him with prizes, decorations, and honorary degrees. Awarded the Nobel Prize in 1969, he chose to accept it only because refusing-as had Sartre a few years earlier-would have aroused more attention. So he sent an envoy to Sweden to accept the check and discreetly distributed the money to those in need.

And yet, as much as Beckett hated the limelight, his desire to withdraw from it makes a fitting metaphor for his peculiar literary achievement.

More here

Friday, June 30, 2006

Watching the Detectives: Richard Linklater adapts Philip K.Dick's "A Scanner Darkly"

from Slate.com

Who is Richard Linklater, really? In the last 15 years he's written and directed great, meandering films about disaffected types who don't do a whole lot of anything besides kicking back and philosophizing (Slacker, Dazed and Confused, Waking Life), but he's also made tightly plotted movies about equally disaffected types who band together to combat a repressive social order (The Newton Boys, Fast Food Nation, even The School of Rock, and Bad News Bears). It's as though the left and right hemispheres of Linklater's brain have been competing! Which is, of course, precisely the problem faced by narcotics agent Bob Arctor, the protagonist of Philip K. Dick's brilliant 1977 science-fiction novel A Scanner Darkly.

So, will Linklater's new, rotoscoped adaptation of A Scanner Darkly, starring Keanu Reeves as Arctor, reveal once and for all which side of Linklater's brain is the dominant one? That is, will Keanu and his drug buddies, played by Robert Downey Jr., Woody Harrelson, Winona Ryder, and Rory Cochrane (reprising his role in Dazed and Confused), get politicized and take action against their not-too-distant-future surveillance society? Or will these slackers stay glued to their couches, entertaining themselves with interminable Linklater-esque bull sessions?

The answer is: both. After all, in what sci-fi fans describe as the "phildickian" worldview, binary opposites—good/evil, real/unreal—are impossible ever to untangle. That's why Arctor has such a tough time deciding whether he's a narc posing as a doper or vice versa ... and that's before he's directed by his narc superiors to set up surveillance on a suspicious doper: himself. In Linklater's Scanner, that is to say, audiences may finally catch a glimpse—even if through a glass darkly—of the director's own paradoxical worldview, one in which slacking is not only a form of political activism but the only possible activism.

In order to get a firmer grasp on this chuckle-inducing notion, it's necessary to revisit the intellectual climate of the mid-1970s, when a middle-aged Dick was playing host to gun-toting drug dealers and their teenage clients, downing gruesome quantities of speed, and working fitfully on Scanner. In those years, socialism as a doctrine and a movement no longer seemed capable of arresting the progress of the insurgent political, economic, and cultural doctrine that during the market-worshiping 1980s would come to be called neoliberalism. Disappointed soixante-huitards everywhere sank into their couches and succumbed to irony and lifestyle radicalism. In France, however (where Dick's fiction was treated with the kind of respect formerly accorded only to Poe), thinkers like Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze, and Félix Guattari offered up theories of how social control was now exercised not through class domination but increasingly subtle mechanisms.

In 1972, for example, Deleuze and Guattari claimed in Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia that Westerners have been "oedipalized" (normalized, trained to desire their own repression) at home, at school, and at work. In '75, Foucault's Discipline and Punish concluded that the modern liberal state was a neototalitarian apparatus designed solely to optimize the economic utility of recalcitrant individuals. Giving up on the workingman, radical intellectuals cast about in unlikely places for a new revolutionary subject. Deleuze and Guattari praised the psychotic as someone incapable of being normalized and suggested that people be "schizophrenized." In Italy, Antonio ("Empire") Negri located the agent of social revolution among those marginalized from economic and political life: the criminal, the part-time worker, the unemployed. And, in a 1977 interview, Foucault said he was looking for "someone who, wherever he finds himself, will pose the question as to whether revolution is worth the trouble, and if so which revolution and what trouble." Lazy, shiftless, half-crazed revolutionaries? Call them: slackers.

By then, Dick had been writing for more than a decade about semi-employed, drug-using, near-schizophrenic schlemiels who through sheer stubbornness and perversity succeeded in their struggle against neototalitarianism and irreality where heroic types had failed. Forget, if you can, that previous Hollywood adaptations of Dick novels have starred the likes of Harrison Ford, Arnold Schwarzenegger, and Tom Cruise: "I know only one thing about my novels," Dick wrote in a 1970 letter addressing himself to critics who didn't like his unglamorous, anti-heroic protagonists. "In them again and again, this minor man asserts himself in all his hasty, sweaty strength." And in a 1972 speech, Dick stole a march on Foucault, et al., by praising the "laziness, short attention span, perversity, [and] criminal tendencies" of the lazy, shiftless, half-crazed American slacker. ("We can tell and tell him what to do, but when the time comes for him to perform, all the subliminal instruction, all the ideological briefing, all the tranquilizing drugs, all the psychotherapy are a waste," insisted Dick. "He just plain will not jump when the whip is cracked.")

It's tricky to portray the slacker's qualities as progressive ones, as Dick was all too aware. And here in our own repoliticized era, when even a Hollywood broadsheet like Variety complains that Linklater's Scanner "misses the boat by not linking its themes more explicitly to the political realities of the present, particularly when issues of unlawful surveillance have rarely been more relevant," convincing American audiences of the virtues of what we might call slacktivism—if we could rid the term of its pejorative connotations—appears impossible. But this is what Linklater has tried to do from the start. For would-be slackers who need pointers on dodging the exploitation of labor, he's directed The Newton Boys, the real-life story of a band of brothers who robbed banks in the 1920s, and The School of Rock, in which Jack Black never once ceases to scheme for ways to avoid holding down a job. And for those of us already convinced of the merits of unwork, he's made Slacker, in which Austin, Texas, is portrayed as a noncoercive utopia dedicated to jawboning; Waking Life, a walkabout in which Wiley Wiggins (Dazed and Confused) gets rotoscoped and enlightened; and other films.

Keanu Reeves may not be a particularly talented actor, but if anyone could make the figure of the slacktivist—part couch potato, part action hero—a compelling and sympathetic one, the star of Bill & Ted's Excellent Adventure and The Matrix is doubtlessly the proper choice. All of which is not to predict that Scanner is going to be Linklater's best film yet, but it might be his most revealing one.

Joshua Glenn

Wednesday, June 21, 2006

Dadaism: Ancestral Cool

What was Dada? What it still is: a word—“hobbyhorse,” in French. Baby talk. Supposedly plucked at random from a dictionary by a coterie of war-evading young writers and artists in Zurich in 1916, “dada” was a two-syllable nonsense poem and a craftily meaningless slogan, signalling a rejection of grownup seriousness at a time when grownups by the million were shooting one another to pieces on the Western Front for reasons that rang ever more hollow. Reason itself was made the scapegoat. “Let us try for once not to be right,” the group’s most influential founder, the Romanian poet Tristan Tzara, urged in a quieter passage of one of his careening manifestos. Dada spread like a chain letter among disaffected bohemians after the war. Wired to self-destruct—“The true Dadas are against Dada,” Tzara enjoined—it was over by 1924, succeeded by imperatives, like those of Surrealism and Constructivism, to be revolutionary in more focussed, even grownup, ways. It wasn’t much of an art movement, though “Dada,” an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, tries hard to make it seem so. (The show originated at the Pompidou Center, in Paris, where it was larger and far more literary in emphasis.) Dada was a publicity movement.

It revelled in novel styles and in popular media—Cubist and Futurist pastiche, collage, assemblage, film, theatre, photography, noise music, sound poetry, puppetry, wild typography, magazines—basically for the hell of it, despite the odd skew, mostly in seething postwar Germany, toward political agitation. Some forms, such as abstraction and machine aesthetics, informed later art; but, as a phenomenon, Dada foretold nothing so much as the marketing of youth fashions. Though hardly commercial, it anticipated a byword of modern advertising: forget the steak, sell the sizzle. The first artist who springs to mind when Dada is mentioned, Marcel Duchamp, would constitute an exception, but he really wasn’t a Dadaist. He had already conceived many of his signature “readymades”—common objects, such as a bottle rack and a snow shovel, presented as art—and his magnum opus, “The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even,” was under way before he had heard of the movement. Apart from accessory japes, like the mustachioed “Mona Lisa” (1919), his relations with Dada were more diplomatic than creative. A vital order of business, in clarifying Dada, is to pry Duchamp from its clutch.

The show is an elliptical tale of six cities: Zurich, where the leading artist was the collagist and sculptor Hans Arp; Cologne, the base of the Surrealist-to-be Max Ernst; Berlin, featuring the satirists George Grosz and Otto Dix; Hannover, the home of the single most substantial artist to emerge from Dada, Kurt Schwitters; Paris, dominated by the poets, in particular André Breton, who would exterminate Dada by folding it into Surrealism; and New York, where the wartime presence of Duchamp, and of the Parisian playboy genius and Dadaist par excellence Francis Picabia and the native prodigy Man Ray, anchored a sparkling salon. (Several figures adorned more than one scene. Arp pops up in Cologne, Hannover, and Paris.) Among a cast of dozens are many who achieved immortality in the brief heat of the movement’s heyday, such as the German polemicist Richard Huelsenbeck, who later became a New York psychiatrist, and others who were just passing through, like the glamorous scamp and potter Beatrice Wood. Collagists abound. The quickest technical route to righteous Dadaism was to snip out printed images and compose them to comic, politically rhetorical, or naughty effect. Such things often have a quality at once piquant and jaded, like the morning-after detritus of what must have been a swell party. Schwitters’s formally rigorous collages of everyday trash—newspaper fragments, bus tickets—are something more. Schwitters, who was also an innovative poet and a pioneer of installation art, developed an anti-conventional aesthetic that proved endlessly fecund—blooming, for example, in Robert Rauschenberg’s “Combines” of the nineteen-fifties.

Dada did not attract artists who earnestly practiced straight painting and sculpture. Most works in those mediums in the MOMA show are mediocre—including Picabia’s, though his paintings of mechanical forms laced with wordplay and sexual innuendo can seem deliberately nugatory, razzing the very notion of quality. Picabia, a rich heir with a weakness for fast cars, was seriously unserious, playing—and living—out a Rabelaisian afflatus of all-around ridicule. (If you yearn to be a Dadaist, ask yourself each morning what Picabia would do.) Man Ray’s amateurish paintings, superb photographs, and gamy found-object pieces similarly strike notes of the right (that is, the wrong) stuff. The show’s main picture-maker is the prolific, personally magnetic, opportunistic Ernst, whose tidily irrational drawings, collages, and paintings of the era—essentially superficial glosses on other people’s ideas—pander to a middling taste. The occasional underrated minor artist, notably Arp’s wife, Sophie Taeuber, pleasantly surprises.

Dadaism was an ancestral vein of cool. Those who wondered what it meant could never know.

Peter Schjeldah

More here

Monday, June 05, 2006

Clive James ~ American Movie Critics: How To Write About Film

Since all of us are deeply learned experts on the movies even when we don't know much about anything else, people wishing to make their mark as movie critics must either be able to express opinions like ours better than we can, or else they must be in charge of a big idea, preferably one that can be dignified by being called a theory. In "American Movie Critics," a Library of America collection drawn from the work of almost 70 high-profile professional critics active at various times since their preferred medium was invented the day before yesterday — the whole history of narrative movies for exhibition still fits inside a mere hundred years — most of the practitioners fall neatly into one category or the other.

It quickly becomes obvious that those without theories write better. You already knew that your friend who's so funny about the "Star Wars" tradition of frightful hairstyles for women (in the corrected sequence of sequel and prequel, Natalie Portman must have passed the bad-hair gene down to Carrie Fisher) is much less boring than your other friend who can tell you how science fiction movies mirror the dynamics of American imperialism. This book proves that history is with you: perceptions aren't just more entertaining than formal schemes of explanation, they're also more explanatory.

The editor, Phillip Lopate, an essayist and film critic, has a catholic scope, and might not agree that the nontheorists clearly win out. They do, though, and one of the subsidiary functions that this hefty compilation might perform — subsidiary, that is, to its being sheerly entertaining on a high level — is to help settle a nagging question. In our appreciation of the arts, does a theory give us more to think about, or less? To me, the answer looks like less, but it could be that I just don't like it when a critic's hulking voice gets in the way of the projector beam and tries to convince me that what I am looking at makes its real sense only as part of a bigger pattern of thought, that pattern being available from the critic's mind at the price of decoding his prose.

For as long as the sonar-riddled soundtrack of "The Hunt for Red October" has me mouthing the word "ping" while I keep reaching for the popcorn, I don't want to hear that what I'm seeing is an example of anything, or a step to anywhere, or a characteristic statement by anyone. What I'm seeing is a whole thing on its own. The real question is why none of it saps my willingness to be involved, not even Sean Connery's shtrangely shibilant Shcottish ackshent as the commander of a Shoviet shubmarine, not even that spliced-in footage of the same old Grumman F9F Panther that has been crashing into the aircraft carrier's deck since the Korean War.

On the other hand, no prodigies of acting by Tom Cruise in "Eyes Wide Shut," climaxed by his partial success in acting himself tall, convinced me for a minute that Stanley Kubrick, when he made his bravely investigative capital work about the human sexual imagination, had the slightest clue what he was doing. In my nonhumble ticket purchaser's opinion, the great Stanley K., as Terry Southern called him, was, when he made "Eyes Wide Shut," finally and irretrievably out to lunch. Does this discrepancy of reaction on my part mean that the frivolous movie was serious, and the serious movie frivolous? Only, you might say, if first impressions are everything.

But in the movies they are. Or, to put it less drastically, in the movies there are no later impressions without a first impression, because you will have stopped watching. Sometimes a critic persuades you to give an unpromising-looking movie a chance, but the movie had better convey the impression pretty quickly that the critic might be right. By and large, it's the movie itself that tells you it means business. It does that by telling a story. No story, no movie. Robert Bresson only did with increasing slowness what other directors had done in a hurry. But when Bresson, somewhere in the vicinity of Camelot, reached the point where almost nothing happening became nothing happening at all, you were gone. A movie has to glue you to your seat even when it's pretending not to.

As the chronological arrangement of this volume reveals, there were good American critics who realized this fact very early on. Several of the post-World War I critics will come as revelations to anybody who assumed, as many of us have long been led to assume, that America was slow to discover the fruitfulness of its own cinema. The usual history runs roughly thus: Even in the Hollywood-haunted America of the years between the wars, the best critics concentrated on the work of obviously major artists, most of them foreign. Then, after World War II, when victory in Europe could well have led the liberated nations to sneer in resentment at the triumph of American might, generous young French critics armed with the auteur theory discovered that a cluster, or pantheon, of directors within the Hollywood system had always been major artists too: Nicholas Ray was up there with Carl Dreyer, and so on. After that, American film criticism grew up to match European maturity.

It took a theory to work the switch, and the essence of the auteur theory was that the director, the controlling hand, shaped the movie with his artistic personality even if it was made within a commercial system as businesslike as Hollywood's. This fact having at last been discovered, film criticism in America came of age. It's a neat progression, but this book, simply by its layout, shows it to be bogus.

Among the early critical big names, some were big names in other fields. Vachel Lindsay and Carl Sandburg were bardic poets, Edmund Wilson was a high-flying man of letters, H. L. Mencken was the perennial star reporter-cum-philologist of the American language, Gilbert Seldes wrote about all of what he christened "the lively arts," Robert E. Sherwood was a Broadway playwright. None of them had any real trouble figuring out what the commercial filmmakers were up to. Edmund Wilson didn't just praise Chaplin at the level due to him, but dispraised Hollywood "gag writers" at the level due to them: he didn't, that is, dismiss them out of hand, but pointed out, correctly, that their chief concern was necessarily with storytelling structures that worked cinematically, and that there might be limitations involved in doing that. There were and there still are.

"Go! Go! Go!" "Five, four, three, two, one!" "Take care of yourself up there/out there/in there." It doesn't matter how formulaic the words sound, because at those moments the movies are essentially still silent. The writing all goes into deciding who falls backward through the window, has his head ripped off by the alien, bares his bottom amusingly to get his shots from the pretty nurse, or pouts tensely when the sonar says "Ping!"

Mencken fancied himself above it all, but he had a penetrating understanding of star power. Sandburg is unreadable today only because of the way he wrote. His prose was bad poetry, like his poetry. ("The craziest, wildest, shivery movie that has come wriggling across the silversheet of a cinema house," he wrote of "The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari," his grammar flapping irrepressibly in the rhetorical wind.) The important consideration here is that everything these superior minds approved of in the foreign art film they also looked for diligently in the American industrial product, and were touchingly glad to find any signs of its flowering.

They were more likely to find those signs, however, if they weren't functioning as general commentators on the arts or as visiting firemen from ritzier boroughs, but had a regular job reviewing the product as it came out. Hence the first critic in the lineup likely to knock the reader sideways is Otis Ferguson, who started reviewing movies for The New Republic in 1934 and kept it up until 1942, the year before his lamentably early death at the age of 36. Had he lived, none of the later pantheon aberration might have got a purchase, because he was perfectly capable of seeing not only that some of the American movies were terrific, but that even the best of them often took a lot more than a director to put together. This last bit was the key perception that the pantheon's attendant incense burners later managed to obscure with wreaths of perfumed smoke, but before we get to that, let's be sure of just how good Ferguson was.

As a first qualification, Ferguson could see that there was such a thing as a hierarchy of trash. He enjoyed "Lives of a Bengal Lancer" even where it was corny, because the corn ("execrable . . . and I like it") was being dished out with brio. This basic capacity for delight underlay the vigor of his prose when it came to the hierarchy of quality, which he realized had its starting point in the same basement as the trash. A Fred Astaire movie was made on the same bean-counting system as a North-West Frontier epic in which dacoits and dervishes lurked treacherously on the back lot, and Astaire wasn't even a star presence compared with a Bengal lancer like Gary Cooper. "As an actor he is too much of a dancer, tending toward pantomime; and as a dancer he is occasionally too ballroomy. But as a man who can create figures, intricate, unpredictable, constantly varied and yet simple, seemingly effortless . . . he brings the strange high quality of genius to one of the baser and more common arts."

Decades later, Arlene Croce wrote about Astaire at greater length, and possibly in greater technical depth, but when she got the snap of his dancing into a sentence, she was following a line that Ferguson had already laid down. Hear how he rounds it out: "Fred Astaire, whatever he may do in whatever picture he is in, has the beat, the swing, the debonair and damn-your-eyes violence of rhythm, all the gay contradiction and irresponsibility, of the best thing this country can contribute to musical history, which is the best American jazz." Take out the word "gay" and it could be something written now, although there aren't many who could write it. Look at the perfect placement of that word "violence," for example. It's not enough to have the vocabulary. You have to have the sensory equipment. You have to spot the way Astaire, in the full flight of a light-foot routine, could slap the sole of his shoe into the floor as if he were rubbing out a bunch of dust mites.

FERGUSON'S sensitivity to the standard output made him more adventurous, not less, when it came to the indisputable works of art. Sometimes it made him adventurous enough to dispute them. He wasn't taken in by the original or the re-edit of Eisenstein's movie about Mexico, which he could see was an incorrigible heap of random footage that would have continued to go nowhere indefinitely if it hadn't been forcibly removed from the master's control. "A way to be a film critic for years was to holler about this rape of great art, though it should have taken no more critical equipment than common sense to see that whatever was cut out, its clumping repetitions and lack of film motion could not have been cut in."

With a good notion of how hard it is to make ordinary film narrative unnoticeably subtle ("story, story, story — or, How can we do it to them so they don't know beforehand that it's being done?"), Ferguson was properly suspicious of any claims that "Citizen Kane" represented an advance in technique. He admired it, but not as a breakthrough: "In the line of the narrative film, as developed in all countries but most highly on the West Coast of America, it holds no great place." A harsh judgment, but Ferguson had put in the groundwork to back it up, and Welles, after the first flush of his apotheosis, might have reached the same conclusion: "The Magnificent Ambersons," even in its unfinished state, is a clear and admirable attempt by the boy genius to get a grip on the technical heritage he had thought to supersede.

One could go on quoting from Ferguson, and expatiating on the quotations, until hell looked like the set of "Ice Station Zebra": there is a book buried in every essay. But the same is true of every good critic. The poet Melvin B. Tolson, who wrote about movies for the African-American newspaper The Washington Tribune, saw "Gone With the Wind" when it came out and reviewed it in terms that could have been expanded into a handbook for the civil rights movement 20 years before the event. One look at the relevant piece will tell you why a critic has to know about the world as well as the movies: Tolson could see that "GWTW" was well made. But he could also see that the script was a crass and callous rewriting of history, a Klan pamphlet in sugared form, a racial insult.

If, then, the selection from James Agee shines out of these pages a bit less than you might expect, it isn't because he's lost his luster; it's because there's so much light from those around him. And Agee, as well as possessing the comprehensive intelligence that the critical heritage had already made a requirement, also possessed an extra quality that we later on, and perhaps dangerously, came to expect from everybody: he had the wit. At the time, it was a first when he wrote this punch line to his review of Billy Wilder's sodden saga about dipsomania, "The Lost Weekend": "I undershtand that liquor interesh: innerish: intereshtsh are rather worried about thish film. Thash tough." Today, you can easily imagine Anthony Lane of The New Yorker doing that. (Lane, being British, isn't in the book, which is a bit like not letting Tiger Woods play at St. Andrews. And Peter Bogdanovich — surely a key figure, and not just as an archivist, in the appreciation of American movies — is another conspicuous absentee. But it's a sign of a good anthology when you start bitching about Who Isn't in It — not a bad title for a book by Bogdanovich, come to think of it.)

And Stanley Kauffmann isn't in it enough. A film critic still in action after more than half a century (most of that time spent at The New Republic), he was the one who took Ferguson's approach, the only approach that really matters, and developed it to its full potential. He knew a lot about every department of the business, but especially acting. He was kind but firm about Marilyn Monroe in "The Misfits": "Her hysterical scene near the end will seem virtuoso acting to those who are overwhelmed by the fact that she has been induced to shout." He could see what was wonderful about Antonioni's "L'Avventura." So could I, at the time; but later, after suffering through "Blowup" and "Zabriskie Point," I started to forget what had once thrilled me. Here is the reminder: "Obviously it is not real time or we would all have to bring along sandwiches and blankets; but a difference of 10 seconds in a scene is a tremendous step toward veristic reproduction rather than theatrical abstraction." (And, he forgot to add, it gives you 10 more seconds to look at a veristic close-up of Monica Vitti, who did to us in those days what Monica Bellucci is doing to a new generation of horny male intellectuals right now.)

Kauffmann had an acute sensitivity to the story behind the technique. It meant that he didn't fail to spot real quality, and it also meant that he was rarely fooled by empty virtuosity. His classic review of Max Ophuls's supposed masterpiece, "Lola Montes," a review mercifully included here as the finale to his oddly meager selection, tells you in advance everything that would be wrong about the auteur theory. Kauffmann could see that "Lola Montes" was indeed the supreme example of Ophuls's characteristic style of the traveling shot that went on forever. But Kauffmann could also see that even if the title role of the bewitching courtesan had been incarnated by a bewitching actress — and Martine Carol, through no fault of her own, was no more bewitching than a bus driver in Communist Kiev — the movie would still have been ruined by its dumb happy-hooker script. In other words, no story.

In Hollywood, for a true masterpiece like "Letter From an Unknown Woman," Ophuls had had the writers, the actors and the right kind of head office breathing down his neck. On "Lola Montes" he was out on his own. The auteur theory depended on the idea that any pantheon director had an artistic personality so strong that it was bound to express itself whatever the compromising circumstances. But all too often, the compromising circumstances helped to make the movie good. That, however, was a tale too complicated to tell for those commentators who wanted to get into business as deep thinkers.

The likelihood that to think deep meant to think less didn't strike any of them until their critical mass movement had worn itself out. Some useful work was done — movies by a cigar-chomping, hard-swearing maverick like Samuel Fuller were resurrected long enough for us all to find out why they had been forgotten — but the absurdities were all too obvious. John Ford's late clunker "7 Women" was praised because it was "Fordian." The adjective they should have been looking for was "unwatchable." Howard Hawks's "Hatari!," in which the same old Hawks plot about John Wayne and the drunken friend and the no-bull broad and the young hotshot and the cackling old-timer was eked out with footage of rhinos and buffaloes, turned out to be quintessentially "Hawksian." And so it went, but it couldn't go on for long, because unless the undiscovered Fordian-Hawksian masterpiece was actually any good, it never got any further than the film societies. As for the articles and the anthologies and the monographs, they never could outweigh the aggregate of ad hoc judgments coming from individual critics. Those judgments might have been right or wrong, but they were seldom crazy, unless the critic had a theory of his or her own.

Some did. Robert Warshow, yet another cultural commentator who died young, wrote a famous long article (which Lopate all too dutifully includes) called "The Gangster as Tragic Hero." Citing but not evoking scores of movies to prove that the American gangster is doomed by the pressures of a society that worships success, it says little in a long space, thereby reversing the desirable relationship of form and content, which, as we have seen, had already been established by critics with fewer pretensions to a sociological overview.

The same could be said, and said twice, for Parker Tyler's equally celebrated long article purporting to show that "Double Indemnity" was always psychologically much more complex than was ever thought possible by those who made it or us who watched. You might have deduced that the claims adjuster Keyes (Edward G. Robinson) was secretly hot for the insurance salesman Neff (Fred MacMurray), but could you ever have guessed that Neff was driven to crime because he had failed sexually with Phyllis (Barbara Stanwyck)? And there we all were thinking he'd succeeded. But stay! For Tyler has some wordplay yet to deploy. "Neff, let us assume, wants permanent insurance against Keyes's subtle inquisition into the ostensible claims of his sexual life." Oh, come on, let's not assume it.

But we don't have to fight for justice very hard, because the fight has already been won by the sanity brigade. Vincent Canby could have won it by himself. There might have been even more here from such informed yet readable solo acts — David Denby, Kenneth Turan, David Thomson and A. O. Scott are only a few of the many recent exponents on the bill — if the worthy bores had not been given their democratic chance, but hey, that's America. Nevertheless, Lopate would have done better to stick to the principle that brevity, up to the point where compression collapses, invariably carries more implication than expansiveness ever can. But he might not have recognized the principle, even while dealing with the best of its consequences. There have been plenty of editors who didn't get it. The legendary William Shawn of The New Yorker never grasped that he was giving Pauline Kael too much room for her own good.

Although Kael knew comparatively little about how movies got made, she was unbeatable at taking off from what she had seen. But beyond that, she would take off from what she had written, and there was a new theory every two weeks. A lot of her theories had to do with loves and hates. She thought Robert Altman was a genius. He can certainly make a movie, but if it hasn't got a script, then he makes "Prêt-à-Porter." That's one of the most salutary lessons of this book: what makes the movie isn't just who directed it, or who's in it, it's how it relates to the real world.

That principle really starts to matter when it comes to movies that profess to understand history, and thus to affect the future. Several quite good critics in various parts of the world knew there was something seriously wrong with Steven Spielberg's "Munich," but they didn't know how to take it down. If they could have put the lessons of this book together, they would have found out how. "Munich" might have survived being directed by someone who knows about nothing except movies. But it was also written by people who don't know half enough about politics. That was why the crucial meeting of Golda Meir's cabinet went for nothing. The movie could have got by with its John Woo-style gunfight face-offs, but without an articulate laying out of the arguments it was a waste of effort.

Similarly, if you know too much about the movies but not enough about the world, you won't be able to see that "Downfall" is dangerously sentimental. Realistic in every observable detail, it is nevertheless a fantasy to the roots, because the pretty girl who plays the secretary looks shocked when Hitler inveighs against the Jews. It comes as a surprise to her.